In today’s fast-paced digital landscape, the demand for applications that are responsive, resilient, and scalable has never been higher. Traditional imperative and blocking programming models, which have served the Java ecosystem for decades, are beginning to show their limitations when faced with the challenges of microservices, cloud-native architectures, and high-volume data streams. This is where Reactive Programming emerges as a transformative paradigm. It offers a new way to think about data flow and concurrency, enabling developers to build non-blocking, asynchronous applications that can handle massive workloads with grace and efficiency. This shift is not just a trend; it’s a fundamental evolution in application design, reflected in the latest Java news and updates across major frameworks. This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Reactive Java, from its core principles and foundational APIs to practical implementations with popular frameworks like Spring WebFlux, and a look at the advanced techniques that will define the next generation of high-performance Java applications.

The Foundations of Reactive Java: Core Concepts and APIs

At the heart of Reactive Java lies the Reactive Streams specification, a standard established to govern asynchronous stream processing with non-blocking backpressure. This specification provides a common ground for different reactive libraries to interoperate. It defines a minimal set of interfaces: Publisher, Subscriber, Subscription, and Processor. Understanding these components is the first step toward mastering reactive programming.

Understanding the Publisher-Subscriber Flow and Backpressure

The core interaction in a reactive system is between a Publisher and a Subscriber. A Publisher is a source of data that emits a sequence of events over time. A Subscriber listens for these events and reacts to them. The magic, however, lies in the Subscription and the concept of backpressure. When a Subscriber subscribes to a Publisher, it receives a Subscription object. Through this object, the Subscriber can signal to the Publisher how many items it is ready to process by calling subscription.request(n). This is backpressure: a flow-control mechanism where the consumer controls the rate of production, preventing the producer from overwhelming it. This is a crucial feature for building resilient systems and a hot topic in Java performance news.

Let’s illustrate this with a concrete example using Project Reactor, one of the most popular reactive libraries in the Java ecosystem news. We will create a custom Subscriber to see the lifecycle methods in action.

import org.reactivestreams.Subscription;

import reactor.core.CoreSubscriber;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

public class BackpressureDemo {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Demonstrating Reactive Stream with Backpressure:");

Flux<Integer> numberFlux = Flux.range(1, 10);

numberFlux.subscribe(new CoreSubscriber<Integer>() {

private Subscription subscription;

private int count = 0;

@Override

public void onSubscribe(Subscription s) {

System.out.println("Subscriber: onSubscribe");

this.subscription = s;

// Request the first 2 items

System.out.println("Subscriber: Requesting 2 items...");

this.subscription.request(2);

}

@Override

public void onNext(Integer i) {

System.out.println("Subscriber: Received item -> " + i);

count++;

// After processing 2 items, request 2 more

if (count % 2 == 0) {

System.out.println("Subscriber: Requesting 2 more items...");

this.subscription.request(2);

}

}

@Override

public void onError(Throwable t) {

System.err.println("Subscriber: Encountered an error: " + t.getMessage());

}

@Override

public void onComplete() {

System.out.println("Subscriber: Stream completed.");

}

});

}

}In this example, the subscriber explicitly requests data in chunks of two, demonstrating how it controls the flow of data from the publisher. This non-blocking, pull-push hybrid model is fundamental to the efficiency of reactive systems and a key piece of Java concurrency news.

Practical Implementation with Spring WebFlux

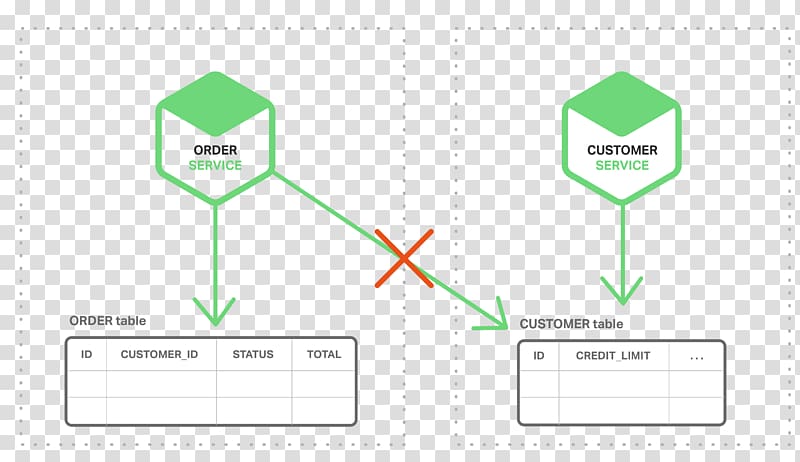

microservices architecture diagram – Event-driven programming Microservices Event-driven architecture …

While understanding the core APIs is essential, the real power of reactive programming shines when integrated into a full-featured framework. The most prominent example in the Java world is Spring WebFlux, the reactive counterpart to the traditional Spring MVC. The latest Spring Boot news is filled with enhancements for its reactive stack, making it easier than ever to build fully non-blocking web applications from the controller down to the database.

Building a Reactive REST Endpoint

Spring WebFlux leverages Project Reactor internally and runs on non-blocking servers like Netty by default. This allows it to handle a large number of concurrent connections with a small number of threads. Let’s build a simple reactive REST controller that streams a list of products. This example assumes you have a Spring Boot project with the `spring-boot-starter-webflux` dependency managed by Maven or Gradle, which is standard practice according to recent Maven news and Gradle news.

import org.springframework.stereotype.Service;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.GetMapping;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.PathVariable;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RestController;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

import reactor.core.publisher.Mono;

import java.time.Duration;

// --- Data Model ---

record Product(String id, String name, double price) {}

// --- Service Layer (simulating a reactive data source) ---

@Service

class ProductService {

private final Flux<Product> products = Flux.just(

new Product("p1", "Reactive Handbook", 49.99),

new Product("p2", "Java Concurrency Guide", 59.99),

new Product("p3", "Microservices with Spring", 69.99)

).delayElements(Duration.ofSeconds(1)); // Simulate network latency

public Flux<Product> getAllProducts() {

return products;

}

public Mono<Product> getProductById(String id) {

return products.filter(p -> p.id().equals(id)).next();

}

}

// --- Controller Layer ---

@RestController

public class ProductController {

private final ProductService productService;

public ProductController(ProductService productService) {

this.productService = productService;

}

@GetMapping(value = "/products", produces = "application/stream+json")

public Flux<Product> streamAllProducts() {

System.out.println("Streaming all products...");

return productService.getAllProducts();

}

@GetMapping("/products/{id}")

public Mono<Product> findProductById(@PathVariable String id) {

System.out.println("Finding product by ID: " + id);

return productService.getProductById(id);

}

}Here, the streamAllProducts method returns a Flux<Product>. Instead of waiting for all products to be collected into a list, Spring WebFlux subscribes to the Flux and streams each Product to the client as it becomes available. The delayElements operator simulates the real-world scenario of a slow data source. A client calling this endpoint would see one product appear every second, drastically improving the perceived performance and time-to-first-byte.

Advanced Reactive Techniques and Operators

The true expressiveness of reactive programming is unlocked through its rich set of operators. These are methods that operate on a reactive stream (a Flux or Mono) to transform, filter, combine, or otherwise manipulate the data flowing through it. This declarative style allows developers to build complex, asynchronous logic in a concise and readable way, which is a significant update compared to the callback-heavy patterns of the past. This evolution is a recurring theme in recent Java 17 news and Java 21 news, which emphasize developer productivity.

Composing Asynchronous Operations with flatMap and zip

Two of the most powerful operators are flatMap and zip. The flatMap operator transforms items emitted by a stream into new streams (Publishers) and then flattens these emissions into a single stream. It’s essential for composing dependent asynchronous operations. The zip operator combines multiple streams by waiting for all sources to emit an item and then combining them into a tuple. Let’s see a practical example where we fetch a user profile and their recent orders (from two different services) and combine them.

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

import reactor.core.publisher.Mono;

import java.time.Duration;

import java.util.List;

// --- Data Models ---

record UserProfile(String userId, String name) {}

record UserOrder(String orderId, String userId, double amount) {}

record UserDashboard(UserProfile profile, List<UserOrder> orders) {}

// --- Mock Services ---

class ProfileService {

public Mono<UserProfile> getProfile(String userId) {

// Simulate a network call

return Mono.just(new UserProfile(userId, "Jane Doe")).delayElement(Duration.ofMillis(100));

}

}

class OrderService {

public Flux<UserOrder> getOrders(String userId) {

// Simulate a network call

return Flux.just(

new UserOrder("o1", userId, 150.0),

new UserOrder("o2", userId, 75.50)

).delayElements(Duration.ofMillis(50));

}

}

// --- Composition Logic ---

public class AdvancedReactiveComposition {

private final ProfileService profileService = new ProfileService();

private final OrderService orderService = new OrderService();

public Mono<UserDashboard> getUserDashboard(String userId) {

// 1. Fetch the user profile

Mono<UserProfile> userProfileMono = profileService.getProfile(userId);

// 2. Fetch the user's orders (dependent on userId, but can run in parallel with profile fetch)

Mono<List<UserOrder>> userOrdersMono = orderService.getOrders(userId).collectList();

// 3. Zip the results together when both are available

return Mono.zip(userProfileMono, userOrdersMono)

.map(tuple -> new UserDashboard(tuple.getT1(), tuple.getT2()));

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

AdvancedReactiveComposition composition = new AdvancedReactiveComposition();

composition.getUserDashboard("user-123")

.subscribe(dashboard -> System.out.println("Dashboard Ready: " + dashboard));

// Keep the main thread alive to see the async result

try {

Thread.sleep(1000);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

}

}This code declaratively defines a workflow: fetch a profile, fetch orders, and once both asynchronous operations complete, combine them into a UserDashboard. This is achieved without blocking any threads, making the application highly efficient and scalable.

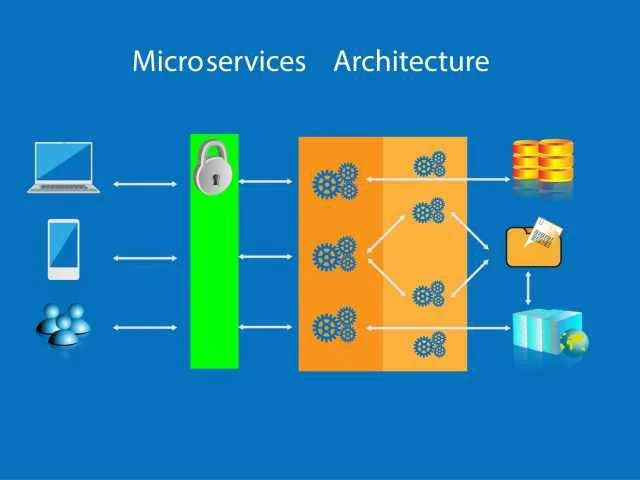

microservices architecture diagram – What are Microservices and Can this Architecture Improve Your …

Best Practices, Pitfalls, and the Broader Ecosystem

Adopting reactive programming requires a shift in mindset. While powerful, it comes with its own set of challenges and best practices. One of the most important pieces of Java wisdom tips news for reactive developers is to never, ever block a reactive pipeline.

Common Pitfalls: Don’t Break the Reactive Chain

The most common mistake beginners make is calling blocking methods like block() or toFuture().get() within a reactive operator like flatMap or map. Doing so occupies a worker thread, defeating the entire purpose of the non-blocking model and potentially leading to thread starvation and deadlocks. Tools like Reactor’s BlockHound can be integrated during testing (a key tip from JUnit news) to detect and fail builds where blocking calls are made on non-blocking threads.

The Expanding Reactive Ecosystem: Jakarta EE and Project Loom

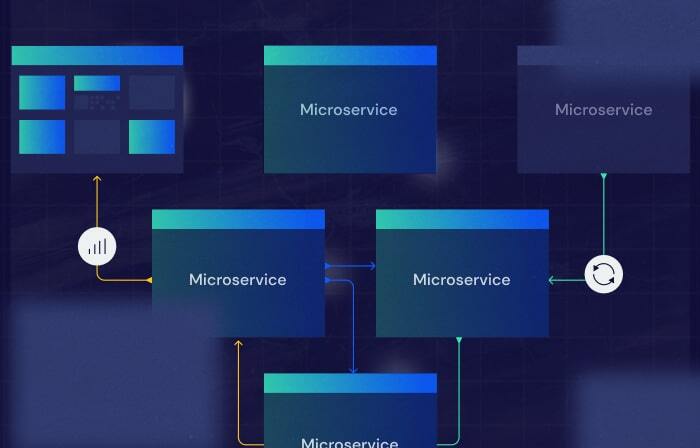

microservices architecture diagram – What are Microservice Architecture – Features and Components

The reactive paradigm isn’t confined to the Spring ecosystem. The latest Jakarta EE news shows significant progress in this area, with specifications like MicroProfile Reactive Messaging and MicroProfile Reactive Streams Operators providing standardized ways for enterprise applications to leverage reactive principles. This allows developers using application servers like Open Liberty or WildFly to build robust, event-driven microservices.

Furthermore, the future of Java concurrency is evolving. A major topic in JVM news is Project Loom, which introduces lightweight virtual threads to the JVM. While reactive programming excels at I/O-bound concurrency, Java virtual threads news suggests that virtual threads will offer a simpler, imperative-style alternative for writing concurrent code that is easier to debug and reason about. The exciting part is that these two models are not mutually exclusive. The future Java landscape will likely see a hybrid approach, where developers choose the best tool for the job, combining the efficiency of reactive streams with the simplicity of virtual threads.

Conclusion: Embracing the Reactive Future

Reactive programming represents a significant and necessary evolution in Java development. By embracing non-blocking, asynchronous principles and a declarative, data-flow-oriented style, developers can build applications that are more resilient, scalable, and efficient than ever before. Frameworks like Spring WebFlux and standards from MicroProfile have made this paradigm accessible and practical for real-world use. While the learning curve can be steep, understanding the core concepts of publishers, subscribers, backpressure, and the powerful operator chain is a crucial investment for any modern Java developer. As the Java platform continues to evolve with exciting developments like Project Loom, the principles of reactive design will remain a cornerstone of high-performance application architecture. The journey into reactive Java is not just about learning a new library; it’s about preparing for the future of concurrent and distributed systems.