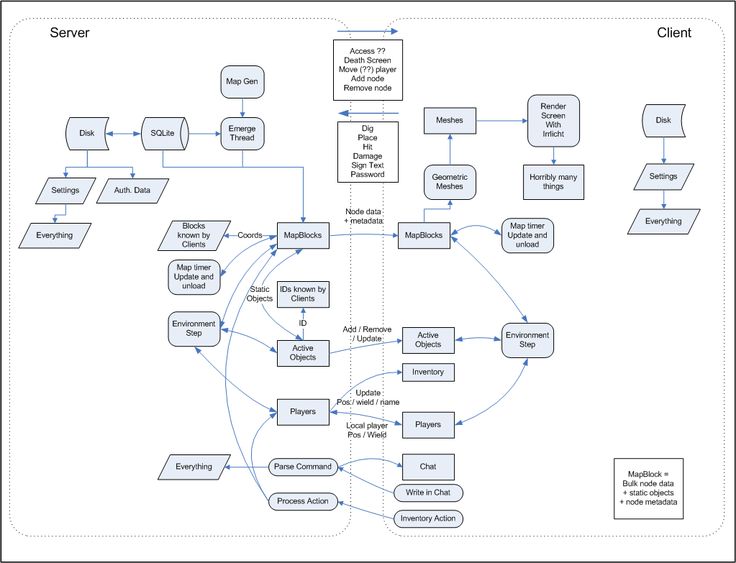

I woke up this morning to my feed blowing up about yet another high-profile reactive project being open-sourced. A big tech player—one that usually keeps its cards close to its chest—finally dropped their internal networking stack on GitHub. It’s fast, it’s built on Netty, and the benchmarks look insane.

My first reaction? Exhaustion.

Don’t get me wrong. I love seeing how the sausage is made at scale. But as a Java developer who has survived the last decade of “Reactive Manifesto” hype, the fragmentation is killing me. We have Project Reactor. We have RxJava (versions 2 and 3, because why not?). We have Mutiny. We have Akka Streams. And now, we have a new contender entering the ring.

The community response was immediate, and honestly, spot on. Instead of just oohing and aahing over the throughput numbers, people started asking: “Does this support MicroProfile APIs?”

That is the right question. In late 2025, if you’re releasing a reactive library that doesn’t play nice with the established standards, you’re just handing us homework. We don’t need another proprietary Publisher<T> implementation. We need interoperability.

The “Publisher” Trap

Here’s the thing. Most of these libraries implement the Reactive Streams specification (the org.reactivestreams interfaces or Java 9’s java.util.concurrent.Flow). That’s the bare minimum. It ensures that backpressure works—that a fast producer won’t drown a slow consumer.

But raw Reactive Streams interfaces are useless for application logic. They have no operators. No .map(). No .filter(). No .flatMap(). If a library gives you a raw Publisher<Data>, you can’t actually do anything with it unless you wrap it in something else.

I ran into this last week. I was trying to integrate a niche database driver that returned its own custom implementation of a Publisher. To transform the data, I had to pull in Project Reactor just to get a usable API.

// The "Integration Hell" we all know

import com.proprietary.driver.CustomPublisher;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

public void processData() {

CustomPublisher<String> source = driver.getDataStream();

// We have to wrap it just to map a string

Flux.from(source)

.map(String::toUpperCase)

.filter(s -> s.startsWith("A"))

.subscribe(System.out::println);

}This works, sure. But now my project depends on the driver and Reactor. If another library I use depends on RxJava 3, I now have two massive reactive engines on my classpath doing the exact same thing. It’s bloat, pure and simple.

Why MicroProfile Reactive Streams Operators Matters

This is where the push for MicroProfile Reactive Streams Operators (MP-RSO) comes in. It’s a boring name for a critical piece of tech. It provides a standard set of builders and operators that work across different implementations.

The idea is that library authors (like the folks behind this new open-source drop) shouldn’t force a specific implementation on us. They should expose their streams in a way that allows us to use standard APIs to manipulate them.

If a library adopts MP-RSO, I can write code that looks like this, regardless of what engine is running underneath:

import org.eclipse.microprofile.reactive.streams.operators.ReactiveStreams;

import org.reactivestreams.Publisher;

public Publisher<String> standardPipeline(Publisher<String> rawSource) {

// This uses the MP-RSO API, not Reactor or RxJava specific APIs

return ReactiveStreams.fromPublisher(rawSource)

.map(String::trim)

.filter(s -> !s.isEmpty())

.flatMap(this::enrichData)

.buildRs(); // Returns a standard Publisher

}The beauty here is decoupling. The ReactiveStreams builder uses java.util.ServiceLoader to find an implementation provider at runtime. If I’m running in Quarkus, it uses Mutiny under the hood. If I’m in a Spring environment (assuming the bridge is set up), it might use Reactor. My code doesn’t care.

The Reality Check: Adoption is Slow

So, why isn’t everyone doing this? Because building a full reactive engine is hard, and building a compliant MP-RSO implementation is even harder.

When a big company open-sources their internal tool, it’s usually highly optimized for their specific use case. They might not need the full suite of standard operators. They just need raw speed for shuffling bytes from Socket A to Socket B.

But here’s my hot take: If you want community adoption in 2025, raw speed isn’t enough. Developer experience (DX) is the bottleneck. If I have to write an adapter layer just to use your “blazing fast” library with my existing business logic, I’m probably just going to stick with what I have.

How to Bridge the Gap (Since We Have To)

Since we can’t force every library maintainer to adopt MicroProfile standards overnight, we often have to do the heavy lifting ourselves. I’ve started using a pattern in my projects to isolate proprietary reactive dependencies.

I create a “Reactive Facade.” It sounds fancy, but it’s basically just a boundary that prevents Flux or Flowable from leaking into my domain logic.

Here is a practical example. Let’s say this new library has a class FastNettyPublisher. I don’t want that class name anywhere near my business services.

import org.eclipse.microprofile.reactive.streams.operators.ReactiveStreams;

import org.reactivestreams.Publisher;

import java.util.concurrent.CompletionStage;

public class IngestionService {

// We accept the generic Publisher interface

public void ingest(Publisher<DataPacket> source) {

// We use the standard MP API to build our processing pipeline

CompletionStage<Void> result = ReactiveStreams.fromPublisher(source)

.filter(packet -> packet.isValid())

.map(packet -> packet.payload())

.forEach(payload -> System.out.println("Processing: " + payload))

.run(); // Executes the stream

result.toCompletableFuture().join();

}

}By coding against the MicroProfile spec, I’ve future-proofed this method. If I swap out the underlying library next year because another “game-changing” tool comes out, this code doesn’t change. I just swap the jar on the classpath.

The “Virtual Threads” Elephant in the Room

I can hear some of you screaming at your screens: “Why are we still talking about Reactive in 2025? Just use Virtual Threads!”

I get it. Project Loom (Virtual Threads) solved the “thread-per-request” scalability issue. For 90% of CRUD apps, imperative blocking code on virtual threads is the way to go. It’s simpler to read, simpler to debug, and simpler to test.

But Reactive isn’t dead. It just moved.

Reactive is still king for streaming data, backpressure handling, and complex event processing. Virtual threads don’t magically handle the scenario where a producer is generating 10,000 events per second and the consumer can only handle 500. You still need flow control. You still need operators to window, buffer, and throttle that stream.

That’s why these new libraries keep popping up. High-performance networking needs reactive patterns. The disconnect happens when those patterns leak into the application layer without a standard API to tame them.

Final Thoughts

It’s cool that companies are sharing their tech. I really mean that. But the Java ecosystem is mature now. We aren’t in the Wild West of 2016 anymore where every library needed to invent its own async primitives.

If you’re a library author reading this: Please, look at MicroProfile Reactive Streams Operators. Or at least provide a native bridge.

And if you’re a dev like me, stuck glueing these things together: Stick to the standards. Your future self (and your poor teammates who have to maintain your code) will thank you when the next “revolutionary” framework drops in six months and you don’t have to rewrite your entire data pipeline.