In the vast landscape of software development, few things are as universally dreaded as the infamous NullPointerException. Often referred to as the “billion-dollar mistake,” null references have been a persistent source of bugs, boilerplate code, and developer frustration for decades. While modern Java versions, particularly since Java 8, have introduced tools like Optional to mitigate this issue, the core problem of representing “nothing” remains. This is where a classic design pattern, the Null Object pattern, offers an elegant and powerful alternative. It reframes the problem entirely: instead of returning a null reference to signify the absence of an object, we return a special object that conforms to the expected interface but does nothing. This simple shift in perspective can dramatically clean up client code, improve readability, and create more resilient systems, a topic of frequent discussion in the latest Java wisdom tips news.

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the Null Object pattern within the context of the modern Java ecosystem. We’ll delve into its core principles, practical implementations in frameworks like Spring Boot, advanced techniques, and critical best practices. Whether you’re keeping up with Java 21 news or maintaining a legacy system, understanding this pattern is a crucial step toward writing more robust and expressive code.

Understanding the Core Concepts of the Null Object Pattern

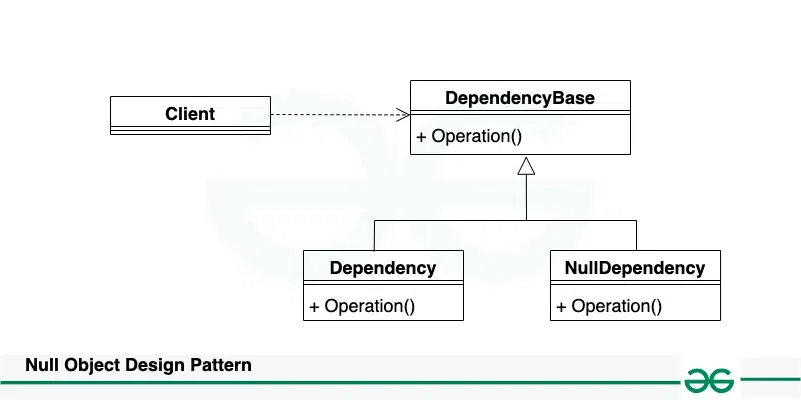

The Null Object pattern is a behavioral design pattern that aims to encapsulate the absence of an object by providing a substitutable alternative that offers default, “do-nothing” behavior. Instead of using a null reference, you use an object that implements the required interface but whose methods are empty or return default values. This allows the client code to treat real objects and null objects uniformly, eliminating the need for constant null checks.

The fundamental problem the pattern solves is the proliferation of conditional logic like if (object != null) { ... } scattered throughout an application. This boilerplate not only clutters the code but also makes it brittle. Forgetting a single null check can lead to a runtime NullPointerException, a bug that can be difficult to trace and fix.

A Basic Example: User Authentication

Consider a simple service that retrieves a user from a database. If the user isn’t found, a common approach is to return null. The client code must then handle this possibility.

Let’s define a common interface:

public interface User {

String getUsername();

boolean hasAccess(String permission);

void grantAccess(String permission);

}A real implementation would look like this:

public class RealUser implements User {

private final String username;

private final Set<String> permissions;

public RealUser(String username) {

this.username = username;

this.permissions = new HashSet<>();

// In a real app, permissions would be loaded from a DB

}

@Override

public String getUsername() {

return username;

}

@Override

public boolean hasAccess(String permission) {

return permissions.contains(permission);

}

@Override

public void grantAccess(String permission) {

System.out.println("Granting permission: " + permission + " to " + username);

permissions.add(permission);

}

}Now, instead of returning null, we introduce a Null Object implementation:

public class NullUser implements User {

@Override

public String getUsername() {

return "Guest"; // Provide a sensible default

}

@Override

public boolean hasAccess(String permission) {

return false; // A "null" user has no permissions

}

@Override

public void grantAccess(String permission) {

// Do nothing. This is the key behavior.

System.out.println("Cannot grant permission: " + permission + ". User is not logged in.");

}

}With this structure, a service method can safely return a NullUser instance instead of null, allowing the client to operate on the returned object without fear of a NullPointerException.

Practical Implementation in a Modern Java Application

Let’s move beyond the conceptual and see how this pattern fits into a typical application built with modern tools. The Spring Boot news and Jakarta EE news often highlight patterns that improve application resilience, and the Null Object pattern is a prime example.

Refactoring a Service Layer

Imagine a CustomerService in a Spring Boot application that retrieves customers. The “before” version might look like this:

Before (with null checks):

// In some controller or other service

Customer customer = customerService.findById(customerId);

if (customer != null) {

System.out.println("Customer Name: " + customer.getName());

if (customer.getAccount() != null) {

customer.getAccount().updateBalance(amount);

}

} else {

System.out.println("Customer not found.");

}

This code is littered with checks. Each level of object nesting adds another potential point of failure. Now, let’s refactor using the Null Object pattern.

First, we ensure our domain objects have Null Object counterparts. We might have a Customer interface with RealCustomer and NullCustomer implementations. The NullCustomer would return default values (e.g., empty strings, zero, or even a NullAccount object).

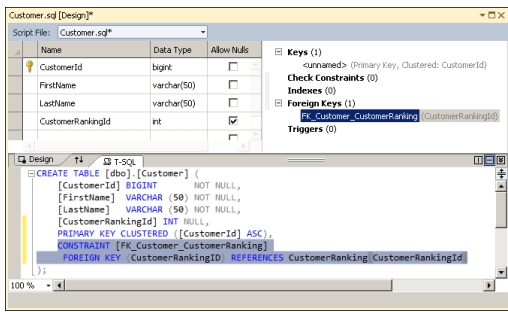

Our refactored CustomerRepository (perhaps using Spring Data JPA or Hibernate) can be modified to return a NullCustomer instead of null or an empty Optional.

@Repository

public class CustomerRepository {

// In a real app, this would be backed by a database (e.g., using Hibernate)

private final Map<Long, Customer> customerStore = new HashMap<>();

private static final Customer NULL_CUSTOMER = new NullCustomer();

public CustomerRepository() {

// Seed with some data

customerStore.put(1L, new RealCustomer(1L, "Alice"));

}

public Customer findById(Long id) {

return customerStore.getOrDefault(id, NULL_CUSTOMER);

}

// NullCustomer implementation

private static class NullCustomer implements Customer {

@Override

public Long getId() { return -1L; }

@Override

public String getName() { return "Unknown Customer"; }

@Override

public boolean isNull() { return true; } // A helper method

@Override

public void processOrder(Order order) {

// Do nothing, or log a warning

System.out.println("Attempted to process order for a non-existent customer.");

}

}

// RealCustomer implementation...

}After (without null checks):

// In the client code

Customer customer = customerService.findById(customerId);

System.out.println("Customer Name: " + customer.getName()); // Safely prints "Unknown Customer" if not found

customer.processOrder(newOrder); // Safely does nothing

The client code is now dramatically simpler and more expressive. It focuses on the business logic without being polluted by defensive programming. This approach is particularly powerful in complex domains where an object can have many collaborators, each of which could potentially be null. This aligns with trends in the broader Java ecosystem news, which emphasize clean, domain-centric code.

Advanced Techniques and Synergies with Other Patterns

The Null Object pattern doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Its power is amplified when combined with other design patterns and modern Java features. As the Java platform evolves, with developments from Project Loom news on virtual threads and Project Valhalla news on value types, the fundamentals of good object-oriented design remain critical.

Singleton Null Objects

Since a Null Object is typically stateless (it has no unique data, only behavior), there is no need to create a new instance every time one is needed. A common optimization is to implement it as a Singleton. This reduces memory allocation and ensures that all parts of the application use the exact same instance for “nothingness,” which can be useful for identity checks (if (user == NullUser.INSTANCE)).

public final class NullUser implements User {

public static final NullUser INSTANCE = new NullUser();

private NullUser() {

// Private constructor to prevent instantiation

}

// ... (do-nothing method implementations)

}

// Usage in a service:

public User findUser(String id) {

// ... logic to find user

if (userFound) {

return new RealUser(id);

}

return NullUser.INSTANCE;

}Combining with the Factory Pattern

A Factory or a Builder pattern is the perfect place to encapsulate the logic of creating either a real object or a null object. This keeps the decision-making process out of your business services and centralizes object creation logic. This is a common pattern seen in projects built with tools like Maven or Gradle, where dependency management and object creation lifecycles are carefully managed.

public class UserFactory {

public static User createUser(String username) {

if (username == null || username.trim().isEmpty()) {

return NullUser.INSTANCE;

}

// Additional validation or data fetching could happen here

return new RealUser(username);

}

}

Null Object vs. java.util.Optional

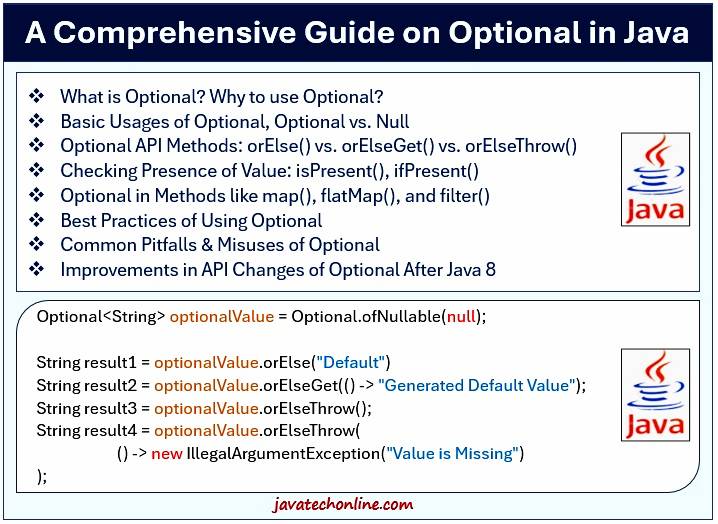

A frequent topic in Java 8 news and subsequent releases is the role of Optional. Isn’t it designed to solve the same problem? Yes and no.

Optionalis a container. It forces the caller to explicitly handle the “absent” case using methods likeifPresent(),orElse(), ormap(). It’s a clear signal in an API’s signature that a value may not be present. It is excellent for return types where the client *must* be aware of and react to the absence of a value.- Null Object Pattern is about polymorphic behavior. It’s best used when the default behavior for an absent object is to simply “do nothing.” The client doesn’t need to be aware that it’s dealing with a special case; it just calls methods as usual.

They can even be used together. A method could return an Optional<User>, and the client could use optionalUser.orElse(NullUser.INSTANCE) to unwrap it into a non-null variable, getting the best of both worlds: a clear API contract and safe, chainable client code.

Best Practices, Pitfalls, and Performance Considerations

While powerful, the Null Object pattern is not a universal solution. Applying it correctly requires understanding its trade-offs and potential pitfalls. Keeping up with Java performance news and best practices is key to using any pattern effectively.

When to Use the Null Object Pattern

- When you have clients that frequently need to check for null before calling methods on an object.

- When the default behavior for a missing object is to do nothing or return a fixed, neutral value.

- When you want to simplify client code and remove conditional clutter.

- In testing scenarios, where providing a Null Object can be simpler than setting up a complex mock with Mockito or other frameworks. It simplifies tests written with JUnit by providing a safe, default dependency.

When to Avoid It

- When the client code *must* react differently if an object is missing. For example, if a user is not found, you might need to throw an exception or redirect to a login page. In these cases, returning

nullor an emptyOptionalis more appropriate because it forces the client to handle the exceptional path explicitly. - When the “do nothing” behavior is not truly neutral. If a Null Object silently swallows actions that should have side effects, it can hide bugs. For example, a

NullLoggermight be fine, but aNullPaymentGatewaythat silently fails to process payments would be disastrous. - It can lead to class explosion if every interface in your system needs a corresponding Null Object implementation. Use it judiciously where it provides the most value.

Tips and Considerations

- Logging: Consider adding logging to your Null Object methods (at a DEBUG or TRACE level). This can be invaluable for debugging, as it makes “doing nothing” a visible event in your logs (e.g.,

log.debug("NullUser: grantAccess called but did nothing.")). - Serialization: If your objects need to be serialized, ensure your Singleton Null Object handles it correctly by implementing the

readResolvemethod to prevent multiple instances from being created upon deserialization. - Performance: The performance impact of using the Null Object pattern is generally negligible and often positive. By avoiding branching (

if/else), you can sometimes achieve better performance due to CPU branch prediction, though this is a micro-optimization. The main benefit is improved code clarity and maintainability, which far outweighs any minor performance differences. This is a recurring theme in discussions around various OpenJDK distributions like Azul Zulu, Amazon Corretto, and Adoptium.

Conclusion: Embracing a Null-Safe Future

The Null Object pattern is more than just a clever trick; it’s a fundamental shift in how we model the absence of data in our domains. By treating “nothing” as a first-class concept with its own behavior, we can write code that is cleaner, more resilient, and easier to reason about. It eliminates entire classes of bugs related to NullPointerException and significantly reduces the cognitive load on developers who no longer have to pepper their code with defensive null checks.

While modern Java features like Optional provide a valuable tool for signaling the potential absence of a value, the Null Object pattern remains a highly relevant and powerful technique for managing default behavior seamlessly. As you work on your next project, whether it’s a complex enterprise system leveraging the latest Spring AI integrations or a simple utility, consider where this pattern can help you model your domain more effectively. By replacing nulls with intelligent objects, you take a significant step toward building more robust and elegant software. The latest Null Object pattern news is that this timeless pattern is more relevant than ever in the quest for safer, cleaner code.