The Reactive Revolution: Navigating the Latest Trends in Java’s Asynchronous Ecosystem

In the world of modern software development, the demand for responsive, resilient, and scalable applications has never been higher. The rise of microservices, real-time data streaming, and cloud-native architectures has pushed traditional blocking, thread-per-request models to their limits. This shift has catalyzed a significant movement within the Java ecosystem news, placing reactive programming at the forefront of innovation. Reactive programming isn’t just a library; it’s a paradigm shift towards building asynchronous, non-blocking applications that can handle massive concurrency with minimal resource consumption.

This article dives deep into the latest Reactive Java news, exploring the core principles, key frameworks like Project Reactor and RxJava, and their integration into the modern Java stack. We’ll examine how reactive concepts are shaping everything from web layers with Spring WebFlux to data access with R2DBC. Furthermore, we’ll discuss the exciting intersection of reactive programming with groundbreaking JVM features like Project Loom’s virtual threads, a hot topic in recent Java 21 news. Whether you’re a seasoned developer or just starting your journey, this guide will provide practical code examples and actionable insights to help you master modern Java concurrency.

The Foundations of Modern Reactive Java

At its heart, reactive programming is about handling asynchronous data streams. Before standardized approaches, developers often found themselves tangled in “callback hell,” leading to code that was difficult to read, maintain, and reason about. The reactive paradigm provides a structured, declarative approach to composing asynchronous and event-based programs.

From Callbacks to Reactive Streams

The turning point for reactive programming in the Java world was the Reactive Streams specification. This initiative, now part of Java 9+ via the java.util.concurrent.Flow API, established a standard for interoperability between different reactive libraries. It defines four simple interfaces:

- Publisher: The source of events. It emits a sequence of items to subscribers.

- Subscriber: The consumer of events. It receives items from a Publisher.

- Subscription: Represents the connection between a Publisher and a Subscriber, used to manage data flow (i.e., backpressure).

- Processor: A stage that acts as both a Subscriber and a Publisher, used for transformations.

This standard ensures that a stream originating from one library (like RxJava) can be seamlessly consumed by another (like Project Reactor), a crucial feature in a diverse ecosystem. This standardization is a significant piece of JVM news that has stabilized the reactive landscape.

Core Building Blocks: Flux and Mono

Project Reactor, the foundation of Spring’s reactive stack, is one of the most popular implementations of the Reactive Streams specification. It provides two primary publisher types that are central to its API:

- Flux: Represents an asynchronous sequence of 0 to N items. It’s perfect for handling collections of data, streams of events, or any sequence that can have multiple values over time.

- Mono: Represents an asynchronous result of 0 or 1 item. It’s ideal for operations that will eventually return a single value or nothing, such as an HTTP API call or a database query for a single entity. This can be seen as a powerful alternative to `Future` or `CompletableFuture`, and a more expressive way to handle optionality than the classic Null Object pattern news might suggest, by using `Mono.empty()` to signify absence.

Here’s a practical example of creating and manipulating a Flux:

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

public class BasicFluxExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Flux<String> userStream = Flux.just("Alice", "Bob", "Charlie", "David")

.map(String::toUpperCase) // Transform each element

.filter(name -> name.length() > 4) // Filter based on a condition

.log(); // Log events for debugging

System.out.println("Subscribing to the user stream...");

userStream.subscribe(

data -> System.out.println("Received: " + data), // onNext

error -> System.err.println("Error: " + error), // onError

() -> System.out.println("Stream completed.") // onComplete

);

}

}

// Console Output:

// Subscribing to the user stream...

// [ INFO] (main) | onSubscribe([Synchronous Fuseable] FluxArray.ArraySubscription)

// [ INFO] (main) | request(unbounded)

// [ INFO] (main) | onNext(ALICE)

// Received: ALICE

// [ INFO] (main) | onNext(CHARLIE)

// Received: CHARLIE

// [ INFO] (main) | onComplete()

// Stream completed.This snippet demonstrates the declarative nature of reactive programming. We define a pipeline of operations (map, filter) that will be executed only when a subscriber attaches to the stream. This lazy execution model is fundamental to reactive systems.

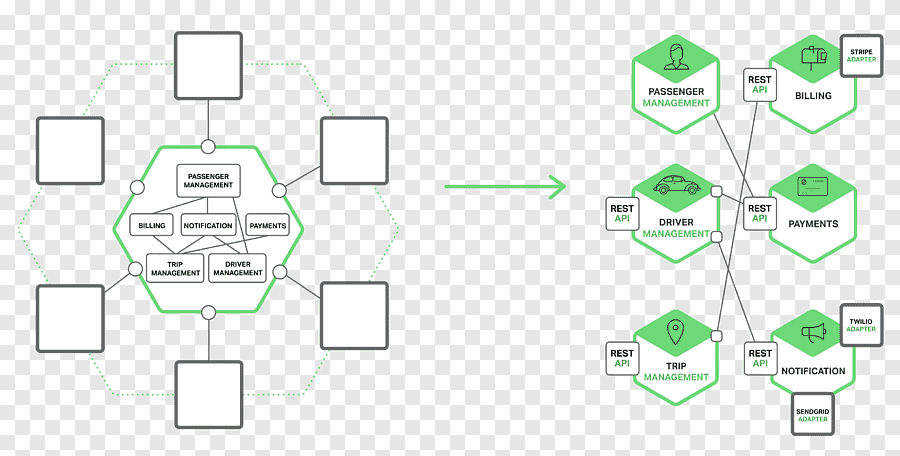

Microservices architecture – Microservices Architecture Architectural style, mobile presntation …

Reactive in the Modern Stack: Frameworks and Integration

The true power of reactive programming is realized when it’s integrated throughout the application stack. The latest Spring Boot news is heavily focused on providing a first-class reactive experience from the web layer down to the database.

Spring WebFlux: The Reactive Web Layer

Spring WebFlux is the reactive counterpart to the traditional Spring MVC. It’s built on Project Reactor and is designed from the ground up to be non-blocking. It can run on servers like Netty, which use an event-loop concurrency model to handle a large number of concurrent connections with a small number of threads. This makes it ideal for building high-performance APIs, especially those involving streaming data like Server-Sent Events (SSE).

Here is an example of a simple reactive REST controller that streams stock price updates every second:

import org.springframework.http.MediaType;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.GetMapping;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RestController;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

import java.time.Duration;

import java.time.LocalTime;

import java.util.Random;

@RestController

public class StockPriceController {

private final Random random = new Random();

@GetMapping(value = "/stocks/live", produces = MediaType.TEXT_EVENT_STREAM_VALUE)

public Flux<String> getLiveStockPrices() {

return Flux.interval(Duration.ofSeconds(1))

.map(tick -> {

double price = 100 + random.nextDouble() * 10;

return String.format("Stock: 'XYZ', Price: %.2f @ %s%n", price, LocalTime.now());

});

}

}When a client connects to the /stocks/live endpoint, they will receive a continuous stream of data without tying up a server thread for the duration of the connection. This is a massive improvement in resource efficiency and a core topic in Java performance news.

Data Persistence with R2DBC

A reactive web layer is only half the story. If your application makes a blocking call to a database using traditional JDBC, the entire non-blocking benefit is lost. This is where R2DBC (Reactive Relational Database Connectivity) comes in. R2DBC is a specification that defines a non-blocking API for database drivers. In contrast to the blocking nature of drivers used by tools like Hibernate (a frequent topic in Hibernate news), R2DBC drivers integrate seamlessly into a reactive pipeline.

Spring Data R2DBC builds on this foundation, providing a familiar repository abstraction for reactive data access. Defining a reactive repository is straightforward:

import org.springframework.data.r2dbc.repository.Query;

import org.springframework.data.repository.reactive.ReactiveCrudRepository;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

// Assuming a 'Product' entity class exists

public interface ProductRepository extends ReactiveCrudRepository<Product, Long> {

@Query("SELECT * FROM products WHERE category = :category")

Flux<Product> findByCategory(String category);

Flux<Product> findByPriceGreaterThan(double price);

}

// Usage in a service:

// productRepository.findByCategory("Electronics")

// .subscribe(product -> System.out.println("Found: " + product.getName()));Notice how the method signatures return Flux and Mono instead of List or a single entity. This allows database operations to be part of the reactive chain without ever blocking the calling thread.

Advanced Techniques and the Evolving Landscape

As developers become more comfortable with reactive principles, they encounter more advanced challenges and opportunities. The Java platform itself is also evolving, creating new dynamics between established paradigms and future-facing features.

Backpressure: The Safety Valve of Reactive Systems

Microservices architecture – What are Microservices and Can this Architecture Improve Your …

One of the most critical concepts in Reactive Streams is backpressure. It’s a mechanism that allows a slow subscriber to control the rate at which a fast publisher emits data. Without backpressure, a fast publisher could easily overwhelm a subscriber, leading to resource exhaustion and application failure. The `Subscription` object is the key, as it allows the subscriber to signal demand by calling `subscription.request(n)`. While frameworks often handle this automatically, understanding it is crucial for building resilient systems.

Here’s a simplified example of a custom subscriber that manually requests items one by one, demonstrating the pull-based nature of backpressure:

import org.reactivestreams.Subscription;

import reactor.core.publisher.BaseSubscriber;

import reactor.core.publisher.Flux;

public class BackpressureExample {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Flux.range(1, 10)

.log()

.subscribe(new BaseSubscriber<Integer>() {

@Override

protected void hookOnSubscribe(Subscription subscription) {

System.out.println("Subscribed! Requesting the first item.");

request(1); // Initial request

}

@Override

protected void hookOnNext(Integer value) {

System.out.println("Processing: " + value);

// Simulate some work

try {

Thread.sleep(500);

} catch (InterruptedException e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

System.out.println("Work complete. Requesting next item.");

request(1); // Request the next item after processing the current one

}

@Override

protected void hookOnComplete() {

System.out.println("Stream is complete.");

}

});

}

}This controlled consumption is essential for stable, production-grade reactive applications.

The Intersection of Reactive and Virtual Threads (Project Loom)

The most significant Java concurrency news in recent years has been the arrival of virtual threads with Project Loom, now a permanent feature in Java 21. Virtual threads are lightweight threads managed by the JVM, allowing developers to write simple, blocking-style code that scales to millions of concurrent tasks. This has led to a vibrant debate: will virtual threads make reactive programming obsolete?

The emerging consensus is no. They are complementary technologies that solve different problems:

- Virtual Threads: Excel at simplifying I/O-bound tasks where the programming model is imperative (“do this, then do that”). It’s about making blocking code non-blocking under the hood. This is a core part of the Java virtual threads news.

- Reactive Programming: Excels at managing complex streams of data and events where the programming model is declarative (“here is the pipeline for processing data as it arrives”). It’s about dataflow, transformations, and managing event streams over time.

Frameworks are already adapting. Spring, for example, is exploring ways to leverage virtual threads to run traditional Spring MVC applications with much higher efficiency. For reactive systems, virtual threads can be used on specific schedulers (`Schedulers.boundedElastic()`) to run short-lived blocking tasks without harming the event loop. The future is likely a hybrid approach where developers choose the right tool for the job, a key takeaway from the latest Project Loom news.

Best Practices for Robust Reactive Applications

Microservices architecture – PDF) Securing Microservices Architecture Using JSON Web Tokens(JWS)

Writing effective reactive code requires a shift in mindset and adherence to a few key principles. Build tools like Maven and Gradle are essential for managing the necessary dependencies, and the latest Maven news and Gradle news often include improvements for handling complex project structures like those found in reactive microservices.

Avoiding Common Pitfalls

- Don’t Block the Event Loop: The cardinal sin in reactive programming is calling a blocking method (like

.block()) on a thread managed by a reactive scheduler (e.g., the event loop). This starves the scheduler of its only thread, grinding the application to a halt. Use tools like Reactor’s BlockHound to detect and prevent such calls during development and testing. - Master Error Handling: Errors in reactive streams are terminal events. A single unhandled exception will terminate the stream. Use operators like

onErrorReturn()(provide a fallback value),onErrorResume()(switch to another stream), orretry()to build resilient pipelines. - Understand Threading: The operators

publishOn()andsubscribeOn()are used to control the execution context (i.e., the thread pool) for different parts of a reactive stream. UsesubscribeOn()to define where the subscription and source emission happens, andpublishOn()to shift the execution for subsequent operators downstream. Misunderstanding these can lead to subtle concurrency bugs.

Tooling and Debugging

Debugging reactive streams can be challenging due to their asynchronous nature and complex stack traces. Use the .log() operator to get a clear view of all the events passing through a stream. For testing, Project Reactor provides the StepVerifier API, which allows you to make assertions about the sequence of events in a stream in a deterministic way. This is a vital tool and an important part of the JUnit news for the reactive world.

Conclusion: The Reactive Future is Bright

Reactive programming has firmly established itself as a cornerstone of modern Java development. It provides a powerful and expressive paradigm for building applications that are not only performant and scalable but also resilient and resource-efficient. Frameworks like Spring Boot have embraced it fully, offering a comprehensive ecosystem with tools like WebFlux and R2DBC that enable developers to build end-to-end non-blocking systems.

The journey doesn’t end here. The ongoing evolution of the JVM, particularly with the introduction of virtual threads in Java 21, is not a threat to the reactive model but an enhancement to the overall concurrency story in Java. The future will see developers leveraging both paradigms, choosing the imperative style of virtual threads for simple blocking I/O and the declarative power of reactive streams for complex event processing. As the Java ecosystem news continues to unfold, staying proficient in reactive principles will be a key differentiator for any developer looking to build the next generation of high-performance applications.